“Store & Scores”

KVM (Ju Huyn Lee & Ludovic Burel)

KVM (Ju Huyn Lee & Ludovic Burel)

Exposition du 13 février au 17 avril 2015

[FR]

L'exposition “Store & Scores” a pour origine une performance intitulée PPKK — Pop and Political Korean Karaoke, que le Korean Vocal Museum a présentée en 2014 à la Fondation d'Entreprise Ricard. Il s'agissait d'une conférence-performance dans laquelle alternaient les prises de paroles discursives – agrémentées de diagrammes (dessinés par la graphiste Sarah Vadé), comme il se doit à l'ère managériale de Powerpoint – et des chansons, des reprises de tubes occidentaux ou orientaux, dont les paroles ont été réécrites, politisées et la musique recomposée (par le designer sonore Géry Petit). Le sous-titre de cette performance était « Chanter Foucault », 2014 étant l'année anniversaire des trente ans de la mort du philosophe. Avec Store & Scores, nous avons souhaité passer de la performance à l'exposition en présentant certaines de ces chansons sous forme d'installation.

Un des points de départ théoriques de cette exposition est « Art and Objecthood » (1967), un texte où le critique d'art moderniste américain Michael Fried déplore la « théâtralité » forcément induite selon lui par les œuvres d'art minimalistes malgré leur revendication de « spécificité », leur quête du « degré zéro » du sens. Pour cette exposition, nous avons créé des dispositifs où la supposée théâtralité de l'esthétique minimaliste est volontairement outrée et magnifiée. Chaque œuvre présentée dans Store & Scores constitue une paradoxale plateforme de karaoké pop et politique. James Meyer, l'auteur de Minimalism, Art and Polemics in the Sixties (2001), pointait lui le facile recodage du minimalisme par le capitalisme marchand, toujours friand de « narrativité » bon marché (storytelling). Il mentionnait à titre d'exemple la reprise du travail de l'artiste américain minimaliste Donald Judd par le designer John Pawson. En 1995, ce dernier associa en effet certaines des œuvres de l’artiste aux dispositifs commerciaux d'une boutique new-yorkaise de Calvin Klein.

Le mimétisme est l'idée-clé de Store & Scores. Nous y reconduisons mimétiquement des displays minimalistes-marchands en les transfigurant en plate-formes de karaoké pop et politique. Dans « De l'homme et du mimétisme : l'ambivalence du discours colonial » (1984), Homi K. Bhabha s'attache à décrire le jeu nécessairement ambivalent de tout processus mimétique (« presque le même, mais pas tout à fait »). Cette équivocité, résultant du nécessaire décalage entre l'identité et la différence, offre un mode de résistance possible à qui refuserait de répondre hystériquement – au sens où, selon Freud, Dora « copie » hystériquement les maux de ventre de sa cousine – à l'injonction mimétique coloniale naguère ou à la prescription néolibérale aujourd'hui. De là l'intitulé, Store & Scores.

Comme dans le film Zombie (Dawn of the Dead) de George Romero (1978), où les zombies consommateurs errent à l'aveugle dans un centre commercial – paradigme du « zombies » dont les anthropologues Jean & John Comaroff font usage pour penser le capitalisme du nouveau millénaire –, le store (le magasin) est l'arkhè (l'archive) dans laquelle nous nous trouvons enfermés aujourd'hui. Il nous faut donc trouver d'autres scores, d'autres partitions, que celles, normatives, qui nous sont proposées. C'est ce jeu conscient de double écriture (de « ressemblance et de menace », de capture et de rupture), ou encore de « sournoise civilité » (sly civility est un autre concept majeur d'Homi K. Bhabha), que Store & Scores met en scène.

Ce karaoké pop et politique témoigne en ce sens d'un clair désir de « séparation des éléments » (partition) – « un rêve de Brecht » disait le dramaturge est-allemand Heiner Müller. La musique, les paroles, la scène, le décor sont à la fois séparés et subsumés sous un seul et un même dispositif (analytique) que le public se doit d'in-terpréter mentalement et recomposer musicalement.

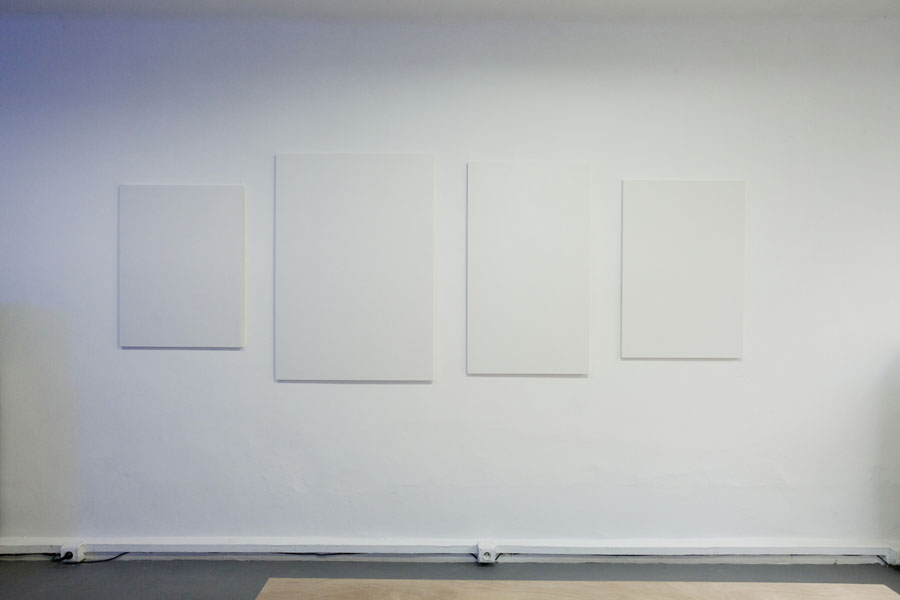

Quelques exemples : l'installation sonore X.E.R.O.S. s'inscrit dans l'héritage minimaliste par ses matériaux, le Plexiglas et le contreplaqué, ici appliqué all over sur trois panneaux muraux bleus, quasi laqués, qui se jouxtent répétitivement. En face de ce dispositif mural, à côté d'un caisson également construit en contre plaqué et Plexiglas bleu, sont posés une ramette de papier A4 où figurent les paroles de la chanson X.E.R.O.S. (une reprise de D.I.S.C.O. d'Ottawan, 1979), ainsi qu'un casque audio branché sur la face bleu-plexi du caisson-boîte à musique d'où sort le son du tube revu et corrigé par le KVM.

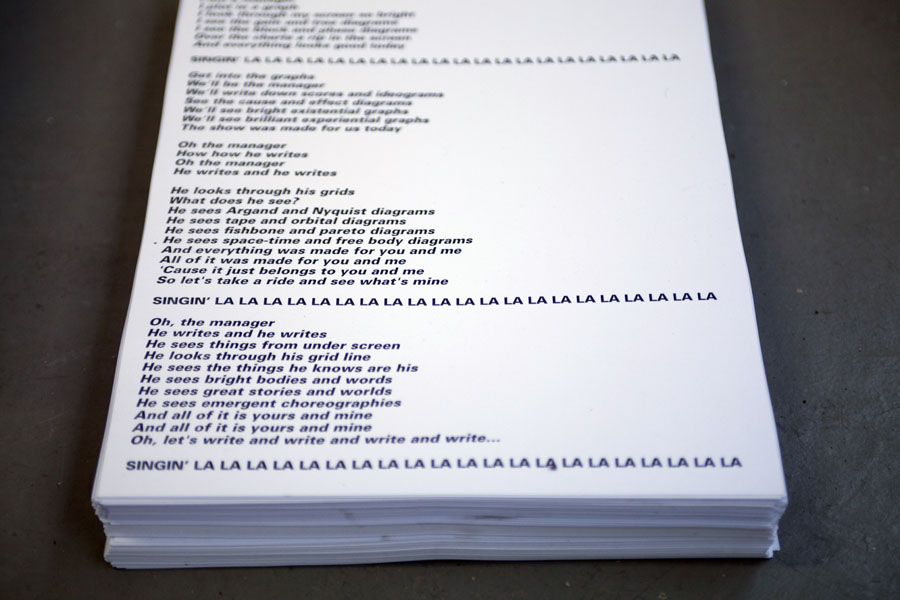

Avec The Manager, c'est le hit pop rock d'Iggy Pop The Passenger de 1977 qui est ici ré-orienté. Le morceau décrit un manager-designer de diagrammes qui reconfigure l'espace urbain (en macro) et les comportements associés (en micro). La notion de « diagramme » a été conceptualisée par Michel Foucault qui, dans Surveiller et punir (1975), l'applique une première fois au camp puis, plus largement, au panoptique de Jeremy Bentham, un dispositif « universel » destiné à la fois à la prison, à l'usine, à l'hôpital, à l'école…

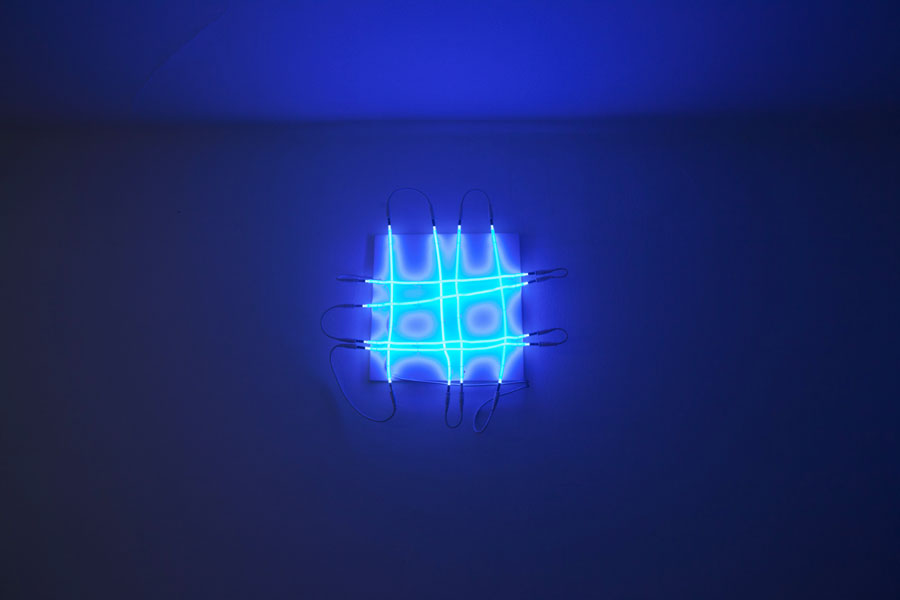

Dans une veine plus erratique, celle de l'esthétique orientale du wabi sabi, deux néons dessinant apparemment une forme de dièse dédoublé – néons réalisés en fait à partir d'une photographie de bidonville grillagé – font le lien entre l'espace-vitrine d'en haut, tout en épure, et l'espace d'en bas, davantage rock & roll.

Dans la cave de la galerie Tator, environnement qui s'apparente à celui d'une « chambre de chansons » – traduction littérale du mot coréen signifiant « karaoké », Noraebang –, le Korean Vocal Museum présente deux autres installations vidéos.

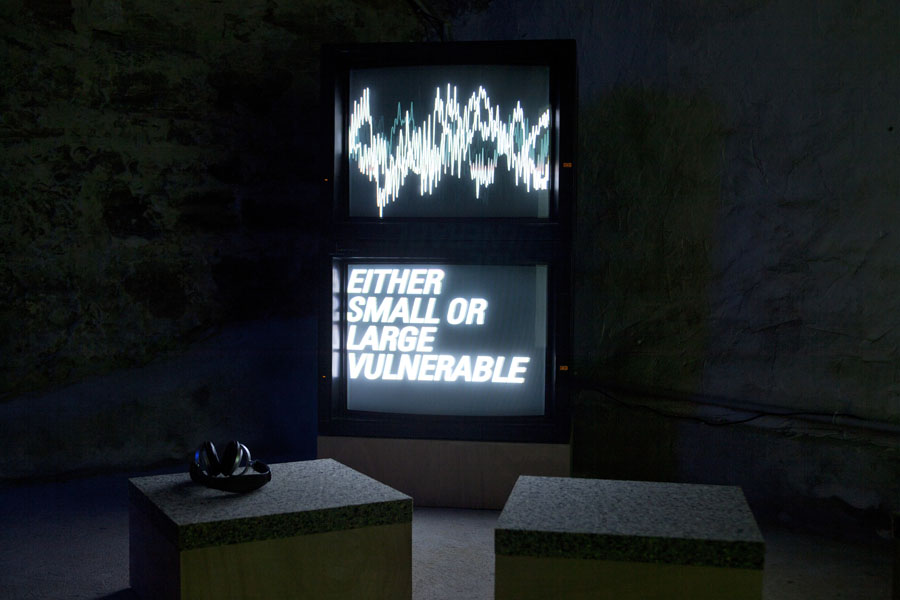

Dans Nov Power, le KVM mêle de manière critique un concept de Michel Foucault et la musique post-punk du groupe Psychic TV (Ov Power, 1982). À travers le « biopouvoir », notion « inventée » par Foucault en 1976 pour qualifier la société post-disciplinaire, celle du contrôle, nous protestons (en chanson) contre le brevetage du vivant – une forme de « design moléculaire de soi et des autres », pourrait-on dire après Foucault.

Dans la continuité, en nous basant cette fois sur les écrits de l'anthropologue Frédéric Keck, qui a appliqué cette notion de biopouvoir au monde animal, nous réinterprétons et requalifions Vitamin C (1972), une chanson du groupe allemand krautrock des années 1970, CAN. Chanson que nous transformons ici en un hymne végétalien, vegan. Les paroles s'affichent progressivement sur un moniteur posé sur un socle bas, associé à des sièges en contreplaqué et mousse agglomérée de vingt et un centimètres de haut, façon assise basse, « orientale ». Moniteur sur lequel repose un autre moniteur, où le rythme de la musique revisitée est visuellement retranscrit sous la forme d'une courbe oscillatoire. Courbe qui pourrait tout aussi bien indiquer le cours d'entre-prises bio-génétiques cotées au Nasdaq que la consommation annuelle de viande au niveau mondial.

Avec Store & Scores, le Korean Vocal Museum réinvestit un dispositif mass-médiatique, le karaoké, conçu au Japon dans les années 1970 pour divertir les salarymen (le mot karaoké signifie littéralement « orchestre vide »), et le subvertit en y injectant des problématiques politiques, par l'entremise de diagrammes – qui sont autant d'« exposition des rapports de forces qui constituent le pouvoir », selon le philosophe Gilles Deleuze, dans son dialogue avec Foucault. Le KVM s'inscrit en porte-à-faux avec la pres-cription mimétique libérale qui, après avoir frappé les populations indigènes en régime colonial, au « siècle des Lumières », caractérise aujourd'hui la néo-middle class planétaire (same same but –not so– different).

Ju Hyun Lee, artiste performeuse, et Ludovic Burel, artiste et éditeur (readit.fr), ont créé en 2012 la plate-forme de recherche KVM, principalement centrée sur la critique sociale du design. Ils ont présenté leurs travaux, sous forme d’installation, lors de Store and Scores (Galerie Tator, Lyon) et Parasite and Mimicry (Centre d’art contemporain de Vilnius, Lituanie) ; d’installations-performances lors de Celebration of the Body #2 (Musée des moulages, Lyon & CAP, Saint-Fons) ; de conférences-performances (Raven Row, Londres ; Artem, Nancy ; Cité du design, Saint-Étienne ; The Book Society, Séoul) et de workshops (D.U. Art, danse, performance, Besançon ; Kaywon School of Art and Design, Séoul). En 2013, ils ont été lauréats du programme Hors-les-murs de l’Institut français (République de Corée). En 2014, leur projet Pop and Political Korean Karaoke a reçu le soutien du Fonds national d’arts graphiques et plastiques (Fnagp), ainsi que du Fonds pour l’innovation artistique et culturelle en Rhône-Alpes (Fiacre).

[EN]

The “Store & Scores” exhibition originates from a performance project entitled “Pop and Political Korean Karaoke (PPKK)”, which the Korean Vocal Museum presented at the Fondation d’Entreprise Ricard in 2014. It was a conference performance that combined discourse –which, in the managerial era of PowerPoint, was of course complemented by diagrams (produced by the graphic designer Sarah Vadé)– and songs: covers of Western and Oriental pop hits, whose music was recomposed (by the sound designer Géry Petit), and the lyrics were rewritten and politicized. The performance’s subtitle was “Chanter Foucault”, as the 30th anniversary of the philosopher’s death was celebrated in 2014. The aim of “Store & Scores” is to take the performance-based project to an exhibition phase, by presenting some of the songs in the form of an installation.

One of the theoretical inspirations of this exhibition is Art and Objecthood (1967), an essay in which the Americanmodernist art critic Michael Fried deplores the “theatricality” that, in his view, is necessarily induced by minimalist art despite the fact that it claims to be “specific” and endeavours to achieve a “fundamental level” of meaning. For this exhibition, we have created devices in which the alleged theatricality of minimalist aesthetics has been deliberately exaggerated and enhanced. Each work presented in the “Store and Scores” exhibition constitutes a paradoxical platform for karaoke pop and politics.

James Meyer, the author of Minimalism, Art and Polemics in the Sixties (2001), highlighted the facile way in which market capitalism –which is always inclined towards cheap “storytelling”– has redefined minimalist art. As an example, he mentioned how the designer John Pawson reused work by the American minimalist artist Donald Judd. In 1995, Pawson integrated some of the artist’s works into the commercial interior of a Calvin Klein store in New York.

Mimicry is the key concept of “Store & Scores”. In the exhibition we have copied minimalist shop displays by transforming them into platforms for karaoke pop and politics. In “On Mimicry and Man: the Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse” (1984), Homi K. Bhabha endeavoured to describe the necessarily ambivalent nature of any imitative process (“almost the same but not quite”). This equivocity, which results from the necessary gap between identity and difference, offers a possible means of resistance to anyone who refuses to respond “hysterically” –in the same way that Freud’s Dora imitated her female cousin’s gastric pains in a hysterical manner– to yesterday’s imitative colonial injunction or today’s neo-liberal dictate.Hence, the exhibition’s title “Store & Scores”.

As in the film Zombie (Dawn of the Dead) by George Romero (1978), in which the zombie-shoppers blindly wander around a shopping mall –a paradigm of the “zombies” on which the anthropologists Jean & John Comaroff based their conception in the new millennium–, the store is the arkhè (archive) in which we are now imprisoned. We therefore need to find “scores” that are different from the normative “scores” that are proposed to us. “Store & Scores” illustrates this conscious presence of dual meanings: “similarity and threat”, “capture and rupture”, and “sly civility”, which is another major concept of Homi K. Bhabha’s work.

Hence, the karaoke pop and politics attest to a clear desire for a “separation of the elements” (score), which, as the East-German playwright Heiner Müller pointed out, was “a dream of Brecht’s”. The music, words, stage, and decor have been both separated and subsumed in one (analytical) device that visitors must interpret mentally and musically reconstruct.

Here are some examples: the sound installation X.E.R.O.S. follows the minimalist approach with its materials: Plexiglas and plywood, which have been used to create three similar and adjoining quasi-lacquered blue mural panels. Opposite this mural device, next to a box that has also been made out of plywood and blue Plexiglas, is a small stack of A4 paper on which is printed the lyrics of the song X.E.R.O.S. (a cover of the 1979 hit D.I.S.C.O. by Ottawan), and a set of headphones plugged into the blue Plexiglas side of the “musical box”, from which can be heard the sound revised and adapted by the KVM.

With “The Manager”, we reorientated Iggy Pop’s “The Passenger” (1977). The former evokes a manager and designer of diagrams who redesigns urban space (macro) and the associated behaviours (micro). The notion of “diagram” was conceptualised by Michel Foucault who, in Survey and Punish (Surveiller et punir, 1975), applied the idea for the first time to a camp then, more broadly to, Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon, a “universal” system that could be applied to prisons, factories, hospitals, and schools.

In a more erratic vein, that of the Oriental aesthetic of simplicity (wabi and sabi), two neons appear to inscribe the shape of a double hash –the neons are, in fact, derived from a photograph of a fenced-off shanty town– and create a link between the upper window space and the lower area, which is more “rock & roll”.

The Korean Vocal Museum is presenting two other video installations in the basement of the Tator Gallery, an environment that resembles a “song room” – a literal translation of Noraebang, the Korean word for “karaoke”.

In “Nov Power”, the KVM has created a critical blend of a concept by Michel Foucault and the post-punk music of the group Psychic TV (“Ov Power”, 1982). Through “bio-power”, a notion “invented” by Foucault in 1976 to describe a post-disciplinary, control society, we are protesting (through song) against the patenting of living things – a form of “molecular design of oneself and others”, one might say, in the words of Foucault.

In the same vein, based on the writings of the anthropologist Frédéric Keck, who applied the notion of bio-power to the animal world, we have reinterpreted and adapted “Vitamin C” (1972), a song from the 1970s by CAN, a German krautrock group. We have transformed the song into a vegan hymn. The words appear gradually on a screen placed on a low stand, complemented by twenty-one-centimetre-high plywood and agglomerated foam chairs, which are low seats in the “Oriental style”. On this screen stands another, on which the rhythm of the revisited music is visually transcrib-ed in the form of an oscillating curve. This curve could just as well represent the prices of bio-genetic companies listed on the Nasdaq as it could the annual global consumption of meat.

With “Store & Scores”, the Korean Vocal Museum has revisited a mass-media phenomenon –karaoke, which was introduced in Japan in the 1970s as entertainment for “salarymen” (the term karaoke literally means “empty orchestra”)–and subverted it by introducing political issues, using diagrams, which provide various ways of “exposing the correlation of forces that constitute power”, in the words of the philosopher Gilles Deleuze in his dialogue with Foucault.

The KVM is at odds with the liberal mimetic dictate that, after being applied to indigenous populations during the colonial regime in the epoch of “the Enlightenment”, today characterises the global neo middle class (same same, but –not so– different).

In 2012, Ju Hyun Lee, a performance artist, and Ludovic Burel, artist and publisher (readit.fr), established the KVM research platform, which mainly focuses on the critique of design. Their work has been presented in various forms: an installation in “Store and Scores” (the Tator Gallery, Lyon, France) and “Parasite and Mimicry” (the Contemporary Art Centre, Vilnius, Lithuania); installation-performances in “Celebration of the Body #2” (the Mouldings Museum of Lyon, France & the Saint-Fons Fine Arts Centre, France); conference performances (Raven Row, London, England; Artem, Nancy, France; the City of Design, Saint-Étienne, France; the Book Society, Seoul, the Republic of Korea). In 2013, they were prize winners of the Institut Français’s “Hors-les-murs” programme (the Republic of Korea). In 2014, their project “Pop and Political Korean Karaoke” received the support of the French National Foundation of Graphic and Plastic Arts (FNAGP) and the Rhône-Alpes Creative Incentive Fund (FIACRE).

Photos © David Desaleux

L'exposition “Store & Scores” a pour origine une performance intitulée PPKK — Pop and Political Korean Karaoke, que le Korean Vocal Museum a présentée en 2014 à la Fondation d'Entreprise Ricard. Il s'agissait d'une conférence-performance dans laquelle alternaient les prises de paroles discursives – agrémentées de diagrammes (dessinés par la graphiste Sarah Vadé), comme il se doit à l'ère managériale de Powerpoint – et des chansons, des reprises de tubes occidentaux ou orientaux, dont les paroles ont été réécrites, politisées et la musique recomposée (par le designer sonore Géry Petit). Le sous-titre de cette performance était « Chanter Foucault », 2014 étant l'année anniversaire des trente ans de la mort du philosophe. Avec Store & Scores, nous avons souhaité passer de la performance à l'exposition en présentant certaines de ces chansons sous forme d'installation.

Un des points de départ théoriques de cette exposition est « Art and Objecthood » (1967), un texte où le critique d'art moderniste américain Michael Fried déplore la « théâtralité » forcément induite selon lui par les œuvres d'art minimalistes malgré leur revendication de « spécificité », leur quête du « degré zéro » du sens. Pour cette exposition, nous avons créé des dispositifs où la supposée théâtralité de l'esthétique minimaliste est volontairement outrée et magnifiée. Chaque œuvre présentée dans Store & Scores constitue une paradoxale plateforme de karaoké pop et politique. James Meyer, l'auteur de Minimalism, Art and Polemics in the Sixties (2001), pointait lui le facile recodage du minimalisme par le capitalisme marchand, toujours friand de « narrativité » bon marché (storytelling). Il mentionnait à titre d'exemple la reprise du travail de l'artiste américain minimaliste Donald Judd par le designer John Pawson. En 1995, ce dernier associa en effet certaines des œuvres de l’artiste aux dispositifs commerciaux d'une boutique new-yorkaise de Calvin Klein.

Le mimétisme est l'idée-clé de Store & Scores. Nous y reconduisons mimétiquement des displays minimalistes-marchands en les transfigurant en plate-formes de karaoké pop et politique. Dans « De l'homme et du mimétisme : l'ambivalence du discours colonial » (1984), Homi K. Bhabha s'attache à décrire le jeu nécessairement ambivalent de tout processus mimétique (« presque le même, mais pas tout à fait »). Cette équivocité, résultant du nécessaire décalage entre l'identité et la différence, offre un mode de résistance possible à qui refuserait de répondre hystériquement – au sens où, selon Freud, Dora « copie » hystériquement les maux de ventre de sa cousine – à l'injonction mimétique coloniale naguère ou à la prescription néolibérale aujourd'hui. De là l'intitulé, Store & Scores.

Comme dans le film Zombie (Dawn of the Dead) de George Romero (1978), où les zombies consommateurs errent à l'aveugle dans un centre commercial – paradigme du « zombies » dont les anthropologues Jean & John Comaroff font usage pour penser le capitalisme du nouveau millénaire –, le store (le magasin) est l'arkhè (l'archive) dans laquelle nous nous trouvons enfermés aujourd'hui. Il nous faut donc trouver d'autres scores, d'autres partitions, que celles, normatives, qui nous sont proposées. C'est ce jeu conscient de double écriture (de « ressemblance et de menace », de capture et de rupture), ou encore de « sournoise civilité » (sly civility est un autre concept majeur d'Homi K. Bhabha), que Store & Scores met en scène.

Ce karaoké pop et politique témoigne en ce sens d'un clair désir de « séparation des éléments » (partition) – « un rêve de Brecht » disait le dramaturge est-allemand Heiner Müller. La musique, les paroles, la scène, le décor sont à la fois séparés et subsumés sous un seul et un même dispositif (analytique) que le public se doit d'in-terpréter mentalement et recomposer musicalement.

Quelques exemples : l'installation sonore X.E.R.O.S. s'inscrit dans l'héritage minimaliste par ses matériaux, le Plexiglas et le contreplaqué, ici appliqué all over sur trois panneaux muraux bleus, quasi laqués, qui se jouxtent répétitivement. En face de ce dispositif mural, à côté d'un caisson également construit en contre plaqué et Plexiglas bleu, sont posés une ramette de papier A4 où figurent les paroles de la chanson X.E.R.O.S. (une reprise de D.I.S.C.O. d'Ottawan, 1979), ainsi qu'un casque audio branché sur la face bleu-plexi du caisson-boîte à musique d'où sort le son du tube revu et corrigé par le KVM.

Avec The Manager, c'est le hit pop rock d'Iggy Pop The Passenger de 1977 qui est ici ré-orienté. Le morceau décrit un manager-designer de diagrammes qui reconfigure l'espace urbain (en macro) et les comportements associés (en micro). La notion de « diagramme » a été conceptualisée par Michel Foucault qui, dans Surveiller et punir (1975), l'applique une première fois au camp puis, plus largement, au panoptique de Jeremy Bentham, un dispositif « universel » destiné à la fois à la prison, à l'usine, à l'hôpital, à l'école…

Dans une veine plus erratique, celle de l'esthétique orientale du wabi sabi, deux néons dessinant apparemment une forme de dièse dédoublé – néons réalisés en fait à partir d'une photographie de bidonville grillagé – font le lien entre l'espace-vitrine d'en haut, tout en épure, et l'espace d'en bas, davantage rock & roll.

Dans la cave de la galerie Tator, environnement qui s'apparente à celui d'une « chambre de chansons » – traduction littérale du mot coréen signifiant « karaoké », Noraebang –, le Korean Vocal Museum présente deux autres installations vidéos.

Dans Nov Power, le KVM mêle de manière critique un concept de Michel Foucault et la musique post-punk du groupe Psychic TV (Ov Power, 1982). À travers le « biopouvoir », notion « inventée » par Foucault en 1976 pour qualifier la société post-disciplinaire, celle du contrôle, nous protestons (en chanson) contre le brevetage du vivant – une forme de « design moléculaire de soi et des autres », pourrait-on dire après Foucault.

Dans la continuité, en nous basant cette fois sur les écrits de l'anthropologue Frédéric Keck, qui a appliqué cette notion de biopouvoir au monde animal, nous réinterprétons et requalifions Vitamin C (1972), une chanson du groupe allemand krautrock des années 1970, CAN. Chanson que nous transformons ici en un hymne végétalien, vegan. Les paroles s'affichent progressivement sur un moniteur posé sur un socle bas, associé à des sièges en contreplaqué et mousse agglomérée de vingt et un centimètres de haut, façon assise basse, « orientale ». Moniteur sur lequel repose un autre moniteur, où le rythme de la musique revisitée est visuellement retranscrit sous la forme d'une courbe oscillatoire. Courbe qui pourrait tout aussi bien indiquer le cours d'entre-prises bio-génétiques cotées au Nasdaq que la consommation annuelle de viande au niveau mondial.

Avec Store & Scores, le Korean Vocal Museum réinvestit un dispositif mass-médiatique, le karaoké, conçu au Japon dans les années 1970 pour divertir les salarymen (le mot karaoké signifie littéralement « orchestre vide »), et le subvertit en y injectant des problématiques politiques, par l'entremise de diagrammes – qui sont autant d'« exposition des rapports de forces qui constituent le pouvoir », selon le philosophe Gilles Deleuze, dans son dialogue avec Foucault. Le KVM s'inscrit en porte-à-faux avec la pres-cription mimétique libérale qui, après avoir frappé les populations indigènes en régime colonial, au « siècle des Lumières », caractérise aujourd'hui la néo-middle class planétaire (same same but –not so– different).

Ju Hyun Lee, artiste performeuse, et Ludovic Burel, artiste et éditeur (readit.fr), ont créé en 2012 la plate-forme de recherche KVM, principalement centrée sur la critique sociale du design. Ils ont présenté leurs travaux, sous forme d’installation, lors de Store and Scores (Galerie Tator, Lyon) et Parasite and Mimicry (Centre d’art contemporain de Vilnius, Lituanie) ; d’installations-performances lors de Celebration of the Body #2 (Musée des moulages, Lyon & CAP, Saint-Fons) ; de conférences-performances (Raven Row, Londres ; Artem, Nancy ; Cité du design, Saint-Étienne ; The Book Society, Séoul) et de workshops (D.U. Art, danse, performance, Besançon ; Kaywon School of Art and Design, Séoul). En 2013, ils ont été lauréats du programme Hors-les-murs de l’Institut français (République de Corée). En 2014, leur projet Pop and Political Korean Karaoke a reçu le soutien du Fonds national d’arts graphiques et plastiques (Fnagp), ainsi que du Fonds pour l’innovation artistique et culturelle en Rhône-Alpes (Fiacre).

[EN]

The “Store & Scores” exhibition originates from a performance project entitled “Pop and Political Korean Karaoke (PPKK)”, which the Korean Vocal Museum presented at the Fondation d’Entreprise Ricard in 2014. It was a conference performance that combined discourse –which, in the managerial era of PowerPoint, was of course complemented by diagrams (produced by the graphic designer Sarah Vadé)– and songs: covers of Western and Oriental pop hits, whose music was recomposed (by the sound designer Géry Petit), and the lyrics were rewritten and politicized. The performance’s subtitle was “Chanter Foucault”, as the 30th anniversary of the philosopher’s death was celebrated in 2014. The aim of “Store & Scores” is to take the performance-based project to an exhibition phase, by presenting some of the songs in the form of an installation.

One of the theoretical inspirations of this exhibition is Art and Objecthood (1967), an essay in which the Americanmodernist art critic Michael Fried deplores the “theatricality” that, in his view, is necessarily induced by minimalist art despite the fact that it claims to be “specific” and endeavours to achieve a “fundamental level” of meaning. For this exhibition, we have created devices in which the alleged theatricality of minimalist aesthetics has been deliberately exaggerated and enhanced. Each work presented in the “Store and Scores” exhibition constitutes a paradoxical platform for karaoke pop and politics.

James Meyer, the author of Minimalism, Art and Polemics in the Sixties (2001), highlighted the facile way in which market capitalism –which is always inclined towards cheap “storytelling”– has redefined minimalist art. As an example, he mentioned how the designer John Pawson reused work by the American minimalist artist Donald Judd. In 1995, Pawson integrated some of the artist’s works into the commercial interior of a Calvin Klein store in New York.

Mimicry is the key concept of “Store & Scores”. In the exhibition we have copied minimalist shop displays by transforming them into platforms for karaoke pop and politics. In “On Mimicry and Man: the Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse” (1984), Homi K. Bhabha endeavoured to describe the necessarily ambivalent nature of any imitative process (“almost the same but not quite”). This equivocity, which results from the necessary gap between identity and difference, offers a possible means of resistance to anyone who refuses to respond “hysterically” –in the same way that Freud’s Dora imitated her female cousin’s gastric pains in a hysterical manner– to yesterday’s imitative colonial injunction or today’s neo-liberal dictate.Hence, the exhibition’s title “Store & Scores”.

As in the film Zombie (Dawn of the Dead) by George Romero (1978), in which the zombie-shoppers blindly wander around a shopping mall –a paradigm of the “zombies” on which the anthropologists Jean & John Comaroff based their conception in the new millennium–, the store is the arkhè (archive) in which we are now imprisoned. We therefore need to find “scores” that are different from the normative “scores” that are proposed to us. “Store & Scores” illustrates this conscious presence of dual meanings: “similarity and threat”, “capture and rupture”, and “sly civility”, which is another major concept of Homi K. Bhabha’s work.

Hence, the karaoke pop and politics attest to a clear desire for a “separation of the elements” (score), which, as the East-German playwright Heiner Müller pointed out, was “a dream of Brecht’s”. The music, words, stage, and decor have been both separated and subsumed in one (analytical) device that visitors must interpret mentally and musically reconstruct.

Here are some examples: the sound installation X.E.R.O.S. follows the minimalist approach with its materials: Plexiglas and plywood, which have been used to create three similar and adjoining quasi-lacquered blue mural panels. Opposite this mural device, next to a box that has also been made out of plywood and blue Plexiglas, is a small stack of A4 paper on which is printed the lyrics of the song X.E.R.O.S. (a cover of the 1979 hit D.I.S.C.O. by Ottawan), and a set of headphones plugged into the blue Plexiglas side of the “musical box”, from which can be heard the sound revised and adapted by the KVM.

With “The Manager”, we reorientated Iggy Pop’s “The Passenger” (1977). The former evokes a manager and designer of diagrams who redesigns urban space (macro) and the associated behaviours (micro). The notion of “diagram” was conceptualised by Michel Foucault who, in Survey and Punish (Surveiller et punir, 1975), applied the idea for the first time to a camp then, more broadly to, Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon, a “universal” system that could be applied to prisons, factories, hospitals, and schools.

In a more erratic vein, that of the Oriental aesthetic of simplicity (wabi and sabi), two neons appear to inscribe the shape of a double hash –the neons are, in fact, derived from a photograph of a fenced-off shanty town– and create a link between the upper window space and the lower area, which is more “rock & roll”.

The Korean Vocal Museum is presenting two other video installations in the basement of the Tator Gallery, an environment that resembles a “song room” – a literal translation of Noraebang, the Korean word for “karaoke”.

In “Nov Power”, the KVM has created a critical blend of a concept by Michel Foucault and the post-punk music of the group Psychic TV (“Ov Power”, 1982). Through “bio-power”, a notion “invented” by Foucault in 1976 to describe a post-disciplinary, control society, we are protesting (through song) against the patenting of living things – a form of “molecular design of oneself and others”, one might say, in the words of Foucault.

In the same vein, based on the writings of the anthropologist Frédéric Keck, who applied the notion of bio-power to the animal world, we have reinterpreted and adapted “Vitamin C” (1972), a song from the 1970s by CAN, a German krautrock group. We have transformed the song into a vegan hymn. The words appear gradually on a screen placed on a low stand, complemented by twenty-one-centimetre-high plywood and agglomerated foam chairs, which are low seats in the “Oriental style”. On this screen stands another, on which the rhythm of the revisited music is visually transcrib-ed in the form of an oscillating curve. This curve could just as well represent the prices of bio-genetic companies listed on the Nasdaq as it could the annual global consumption of meat.

With “Store & Scores”, the Korean Vocal Museum has revisited a mass-media phenomenon –karaoke, which was introduced in Japan in the 1970s as entertainment for “salarymen” (the term karaoke literally means “empty orchestra”)–and subverted it by introducing political issues, using diagrams, which provide various ways of “exposing the correlation of forces that constitute power”, in the words of the philosopher Gilles Deleuze in his dialogue with Foucault.

The KVM is at odds with the liberal mimetic dictate that, after being applied to indigenous populations during the colonial regime in the epoch of “the Enlightenment”, today characterises the global neo middle class (same same, but –not so– different).

In 2012, Ju Hyun Lee, a performance artist, and Ludovic Burel, artist and publisher (readit.fr), established the KVM research platform, which mainly focuses on the critique of design. Their work has been presented in various forms: an installation in “Store and Scores” (the Tator Gallery, Lyon, France) and “Parasite and Mimicry” (the Contemporary Art Centre, Vilnius, Lithuania); installation-performances in “Celebration of the Body #2” (the Mouldings Museum of Lyon, France & the Saint-Fons Fine Arts Centre, France); conference performances (Raven Row, London, England; Artem, Nancy, France; the City of Design, Saint-Étienne, France; the Book Society, Seoul, the Republic of Korea). In 2013, they were prize winners of the Institut Français’s “Hors-les-murs” programme (the Republic of Korea). In 2014, their project “Pop and Political Korean Karaoke” received the support of the French National Foundation of Graphic and Plastic Arts (FNAGP) and the Rhône-Alpes Creative Incentive Fund (FIACRE).

Photos © David Desaleux